|

Historical HighlightsThe Ice Harvester of Burden Lake |

William Mixter Green, Jr., was born in a farm house on Burden Lake in 1916 – which makes him 90 years old, and one of the few residents of the Town of Sand Lake to have fully experienced the change from rural to suburban life. Bill’s father, William Mixter Green, Sr., was born in 1867 and so was in middle age when he married for a second time (his first wife had died in the flu epidemic of 1913) and had a fourth son. Bill’s older half-brothers were carpenters: Arthur lived in West Sand Lake; Harry William lived for a time in Michigan and returned to the area in 1927; Harold worked for the Town of East Greenbush. Bill Senior’s father, Rilson Green, was born in 1829 – and so just three generations of Greens spanned an America from whale oil lamps to personal computers. Rilson became a wheelwright in Conway, Mass., but returned to the Troy area and married Josephine Mixter in 1852. Josephine’s brother Philip Mixter had just finished work, in 1851, on Henry Burden’s water wheel – the largest in the world. He used to talk about the visit of George W.G. Ferris to the water wheel (before it stopped turning in 1894) to help him design the Ferris Wheel that was built in 1893 for the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. When the Greens bought the Burden Lake farm (the house still stands on the west side of Burden Lake Road, near the intersection with Gundrum Road, but the barn behind the house was demolished in 2005) they began several enterprises. One was market gardening – primarily tomatoes and corn (most popular was the “golden bantam” a small ear that’s no longer grown) – for produce that could be sold to cottagers. One was a greenhouse business they called “Say It With Flowers” – primarily geraniums, lilies and cineraria; plants that didn’t sell locally were taken to the Albany market at the site of today’s Pepsi Arena [now Times Union Center]. |

|

|

|

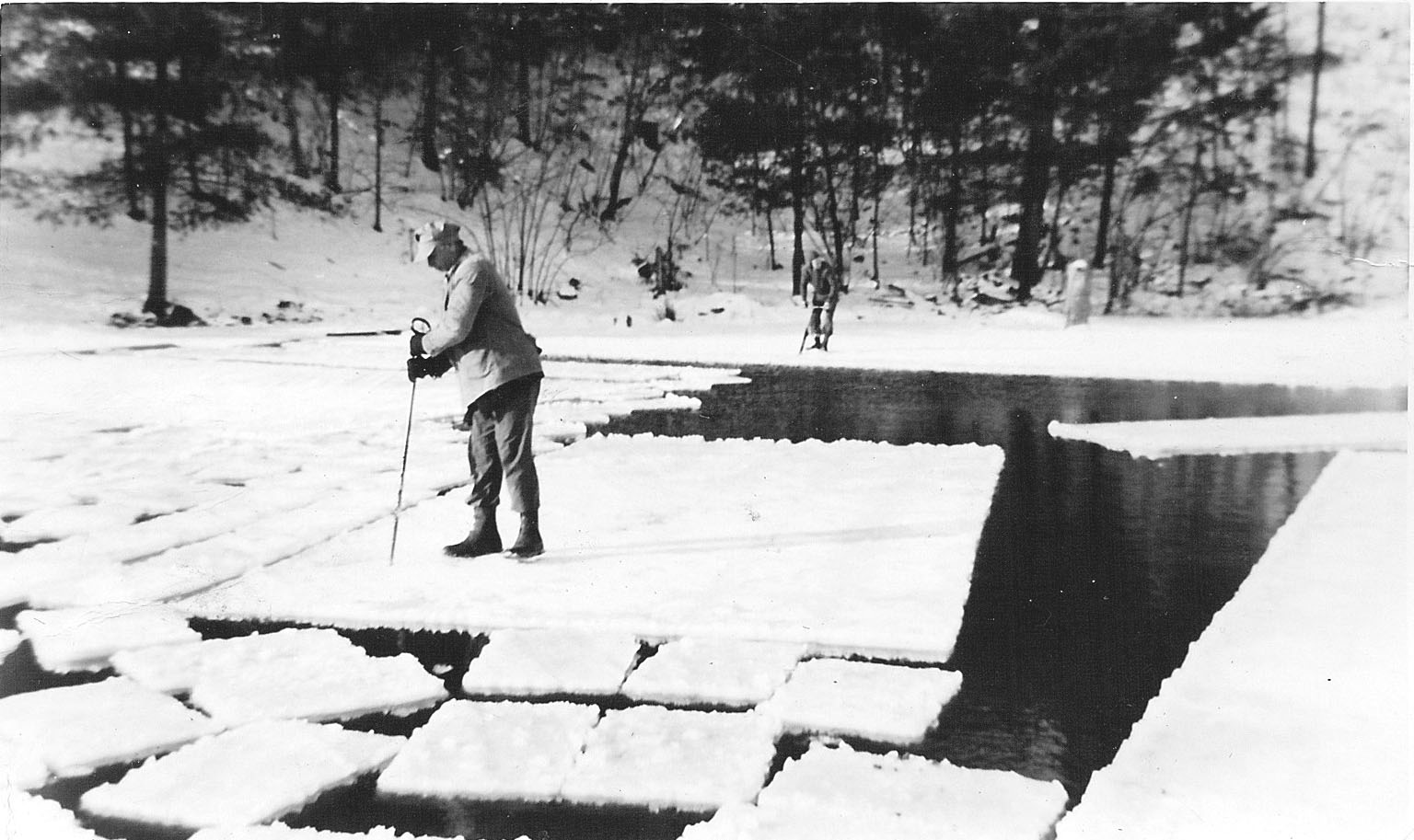

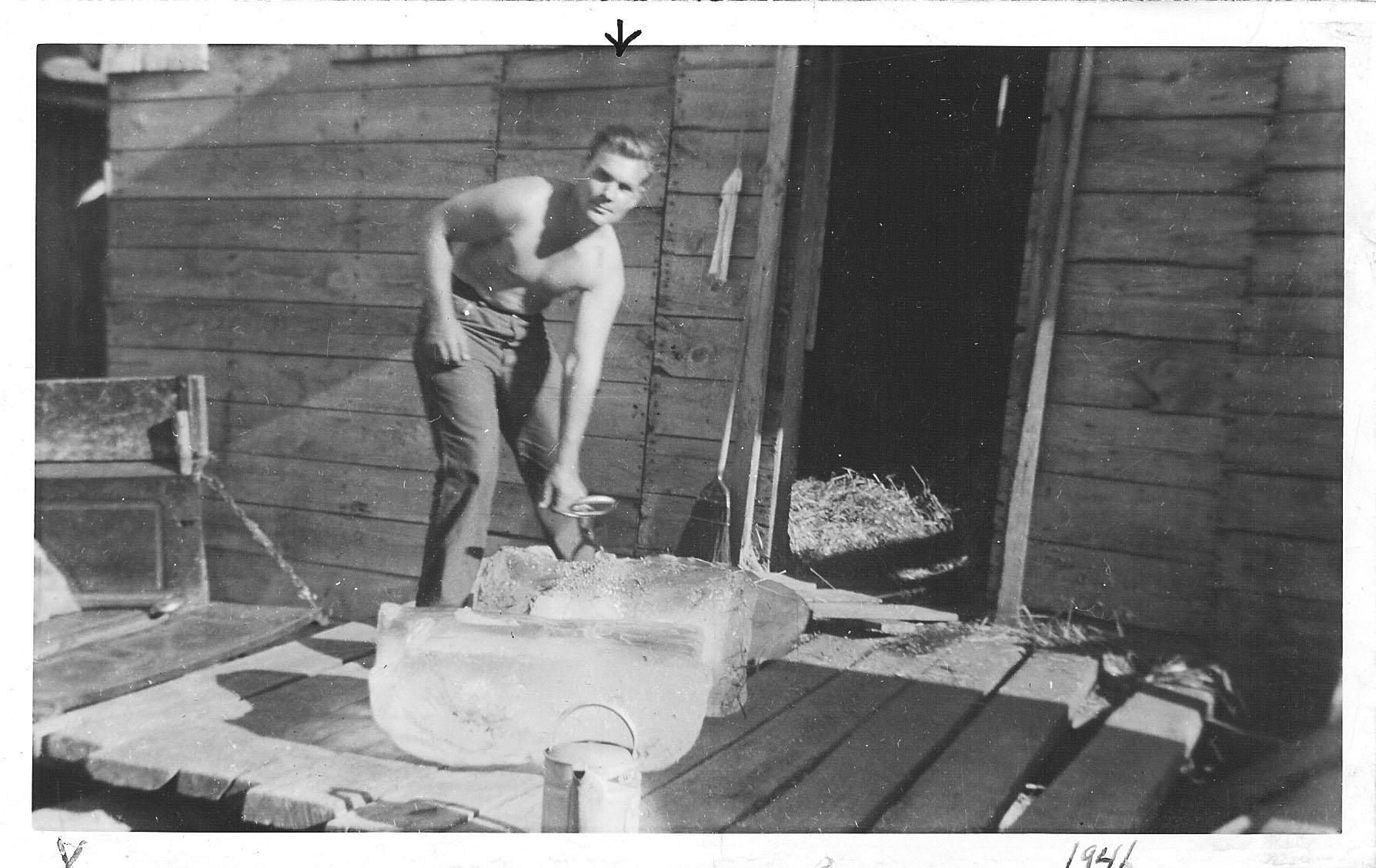

A third enterprise was ice harvesting. Above their house in elevation and to the west was a spring-fed pond, and there they built an ice house to store the product of winter freezes – of the pond first and then of the lake. All dairy farmers had an ice house to keep their milk cool and paid 5 cents a cake for lake ice, but an opportunity for more profit was offered by the explosion of cottage building after World War I - vacationers paid 15 cents for 25 pounds or 25 cents for 50 pounds. The Gundrum family also had an ice harvesting business and it evolved that they would peddle ice to the summer residents of Third Burden Lake, while the Greens covered First and Second Burden Lakes. If they ran out of ice they bought from Millhizer’s on Route 66 in Wynantskill. Bill grew up working all aspects of the farm, but he says he found the greenhouse business too “puttery” and, though he liked the growing of hay and corn, his favorite part of farming was the ice harvest. For optimum product, the ice had to be 12 inches thick – though it was safe for a horse (the horses were smaller then) to walk on at 3 inches at zero degrees Fahrenheit. Bill and his father (or, later, a neighbor) would score off 32 inch by 22 inch by 12 inch thick blocks that would weigh 300 pounds, and then these they would subdivide into 6 50-pound blocks – just the size for a commercial icebox. |

|

|

|

They would harvest in a grid that they kept surrounded by an avenue of open water so they could float the blocks to shore. The avenue would freeze over at night, so the first task was to break this thinner ice – which had the added benefit of squaring up the edges that had, inevitably, become rounded from the pressure of removing blocks the day before. At the end of a day’s harvest, blocks would be set up on end along the edge of the open water to make sure no one would fall in. Bill fell in once on a -10°F day because of the treacherous rounded edge. He was backing up from getting the horse set on the lakeshore, lost his footing and fell in – saving himself from going under by bracing his ice pick across the opening. The shock took his breath away so that he couldn’t even call for help – but Ralph Gundrum rescued him soon enough that after a change of clothes he returned to the day’s harvest. |

|

|

|

Harvesting the pond ice meant skidding the blocks down to the ice house – where they would be stacked to within 6 inches of the siding, and then that space would be filled in with sawdust, and straw spread over the whole pile. Harvesting the lake ice meant hauling the blocks out with a horse and sledge – a man would have to step on the downside until there was enough grip to pull the block out of the water. But the best part of the business was peddling the ice in the long summers on Burden Lake – first by wagon and then by truck. The area then was a bustling destination for day-trippers and cottagers – there was much more public gaiety than now, with several swimming areas open to all and several places where you could rent boats for fishing (Chet Harrington had at least 20 for rent; Will Collins had 2 or 3). Many summer businesses were open along Burden Lake Road. Beginning at the north end, just before First Burden Lake and on the east side, there was Hoffman’s the butcher who would deliver meat to your door, and in his basement was a small tavern. Then at the corners with First Dike Road, there was the Maple Grove Inn – with a very large bar (they had an ice house but didn’t maintain it well, so Bill kept the bar supplied with shaved ice), and behind it a public beach that was usually solid with people. On Sheer Road facing the triangle there was Haynor’s ice cream store with a nickelodeon as an added attraction. |

|

On First Dike Road George Bruegel ran a fishing supply shack he called Fisherman’s Rest, which was much added onto and altered to produce the Burden Lake Casino (which burned down in 1957). During Prohibition in the 1930s, the Casino was hopping – with chorus girls imported to dance to Felix Ferdinando and his Orchestra. From the telephone switchboard in Averill Park a line was strung to the Casino so that the music could be broadcast over WGY. The Casino bar had a large cooler with beer kegs on the bottom that was on Bill’s regular ice run. One morning he discovered that government Revenuers had raided the night before and smashed the kegs, so that his first job was cleaning up the mess of spilled beer. On Second Burden Lake there was Calkins Hotel. When it burned, Minko’s Inn was created out of the hotel barn, offering a bar and dance floor – which now is Kay’s Famous Pizza. Bill remembers the efforts to renovate the barn – Minko used railway ties for the floor (which helps explain the familiar slants). Dan Derby made a name for himself at Minko’s as the singing waiter. |

|

On Third Burden Lake was Hogarty’s Hotel – served more from Nassau and its trolley line than from Averill Park. The Albany and Hudson line went through East Greenbush and East Schodack, Nassau, North Chatham to Kinderhook Lake where there was the popular “Electric Park.” The Troy and New England line would come from Albia through Brookside Park, in front of the Grange Hall to Journey’s End, and then past the Sunset Terrace cottages in Averill Park to the depot on Orient Ave. Vacationers would arrive by trolley and take jitneys to the hotels. Third Burden Lake also had Totem Lodge, a large resort for Jewish people from New York city. They had their own very large ice house, so Gundrum didn’t deliver to them. Other Jewish families rented or owned cottages, and would hire Bill to light their cook fires on their Sabbath Saturdays. There was also a Jewish cottage colony called Smith’s Farms on Central Nassau Road. Totem Lodge’s season began Memorial Day weekend and Bill remembers that they would rent all the United Traction buses to bring guests from the railway depot in Albany to Averill Park and then down Burden Lake Road – which, because of the mills, was the best road. The Swartz farm on Millers Corners Road (the farm house is still there) was purchased for the golf course at Totem Lodge. Entertainment there was big time: Eddie Cantor and Bing Crosby – until World War II. A fire in 1948 essentially ended the resort. Bill, like all the farm youths, volunteered to fight fires. Fire wardens would come by to round them up and they would fight with ‘Indian tanks’ of water slung on their backs and with rakes. In 1954 Bill joined the Best-Luther Volunteer Fire Brigade – and he still is Captain of their Fire Police (the day before this interview he was directing traffic on Route 43 when a large truck overturned at the intersection with 351!) Bill attended the school at Millers Corners, walking there every day. He remembers that one cold winter day he rode a steam engine to class – Nassau was having road work done beginning near Spring Brook Road where the town boundary with Sand Lake is. The schoolmistress lived near Devereaux’ mill on Millers Corners Road. She taught 16 pupils – the oldest helping with the younger, familiar with all the lessons overheard since grade one. There was a box stove in the center of the room, stoked by the older boys – though the firewood was provided and the stove lit in the morning by a school trustee. Each morning, two students would take a stick with a hook at the end and a pail to a neighbor’s well to fetch the day’s drinking water. As with many farm youths, Bill didn’t go to high school. There were several of these one room schools in the area: there was one on Sheer Road just before Biittig Road near fireman’s pond; the Holcomb School on First Dike Road near Methodist Farm Road; the Slab City School off Central Nassau Road; one where the VW vans are parked on Hoag's Corners Road; one on Best Road near Barnes; one at the corner of Werking and Best Roads now a house; the North Nassau school has recently been moved to Mud Pond Road and restored; one at Sliter’s Corners is still standing (as of the writing of the original piece; it has since been demolished), as is one at the intersection of routes 150 and 151; the East Greenbush firehouse was a school, as was the old firehouse at Luther (where Bill’s daughter Linda remembers having Halloween parties). Bill’s summer days would begin with the peddling of ice, and end with cutting wood or hay; as his winter days would begin with ice fishing (you were allowed to put in 15 tip-ups then) and ice harvesting, and end with cutting wood. Calkins also had a hotel in Minerva NY and when, after his Burden Lake place burned, he decided to log the hemlock and pine of his woodlot, he brought a portable sawmill down from Minerva. But the Adirondack men didn’t want to work down south, so Ralph Gundrum and Bill signed up to do the job over several winters. Bill thinks that some of the hemlock went to a shoe factory for boot heels. Bill’s farm activity kept him away from the war effort in World War II. Bob Gundrum and Bill Coey actually tried to enlist in the Army at Troy but were refused, as agricultural work was an essential industry. For a while Bill raised pigs to supply Tobin with pork, but the pigs began to forage in people’s garbage and Tobin refused them. The post-war period was a time, for the farmers of Burden Lake, of government regulations becoming more strict and their way of life more tenuous. Dairy regulations about the electric cooling of milk ended the ice industry in 1946; Bill and the Gundrums had stopped using horses in 1945 when gas rationing ended. Tobin put an end to the pork business. About the same time, Bill moved to a farm on Collins Road that his father had bought in the early 1930s (the family had been keeping both going through the Depression and the War). Bill bought a truck to do what ice deliveries remained, and then turned that into a livelihood hauling for the construction trade. As he put it, a neighbor who was doing that came home fed up one day and said he quit. So Bill took over. In 1952 (the year of the hurricane) he helped his two half brothers build several houses for the Hoffmans of car wash fame. He hauled for the construction of Memorial Nursing School, and for Schaefer Brewery. A Castleton guy hired him to haul lumber from ships at the port of Rensselaer to the site of the new Thruway bridge. Bill tells the story of having to back his truck over a 10-foot-wide grating crossing the river and then having to gingerly get out of the cab and crawl over the top of the load to release the chain. In Spring, Bill still makes his own maple syrup (which he eats on oatmeal 365 mornings a year). This year (2006) he had 50 taps and made 10 gallons of syrup with his great-grandson Nick, age 13, and Nick’s twin sisters who are 11. Bill has a shanty in his maple grove, with a canvas top that he replaces, and a furnace made by his son Bob from a 75 gallon corn syrup drum. In the old days, he would whittle the taps from sumac branches hollowed out with hot metal rods and would use empty honey pails to collect the sap. He thought his great grandkids, who live in Cape Cod, should see how a modern operation produces syrup but, after such a visit, they proclaimed that the old way was more fun. And so Bill makes it seem. Five years ago, when bad knees meant that he had to walk on crutches to tap his trees, Bill decided he would go for a knee replacement operation. And then had a second one the next year. He says that his impression of doctors is that when they shake your hand, there goes $500! When you shake Bill’s hand, you feel in his large grip the power of all those hours of labor that he relished – all those ice blocks that melted through funnels beneath food safes into holes bored in cottage floors; all those ears of corn enjoyed at summer picnics; all those gallons of syrup on morning oatmeal. [Note: William M. Green, Jr. passed away in 2015 at the age of 99.] — The above is a condensing of an interview conducted by Diane DeBlois and Rebecca Harrison in West Sand Lake, Tuesday, May 2, 2006. Both the video tape and the audio tape are deposited with the Sand Lake Historical Society. © 2006, from Historical Highlights, Volume 33, Number 1, Fall 2006 |

|

|

|

|